Share

Introduction

It can be difficult to comprehend the concept of Bitcoin. Its nature is often shrouded in speculation, especially regarding its purpose and ramifications on the global financial system and society as a whole. This speculation breeds uncertainty about Bitcoin’s risks and the tools necessary to protect oneself against them. This piece will aim to separate Bitcoin from NBCAs and traditional assets through identifying its idiosyncrasies and idiosyncratic risks. Subsequently, mitigation treatments to lessen the impact of Bitcoin’s idiosyncratic risks will be discussed, and the severity and probability of these risks following implementation of these mitigation measures will be evaluated.

Bitcoin’s Idiosyncrasies

Bitcoin’s idiosyncrasies are the factors that differentiate Bitcoin from NBCAs. They are summarised by Farrington et al as the combination of the following five factors:

- Proof-of-work (PoW) algorithm

- Difficulty adjustment

- Native unit of monetary value

- Lack of a specifically identifiable founder

- Economic incentive created for distrusting individual actors

Whilst other assets may exhibit a few of the above, none combine all five. A sixth factor not explicitly mentioned by Farrington et al is Bitcoin’s uniquely fair launch, which is a factor few, if any, NBCAs can claim to have.

Proof-of-work (PoW) Algorithm

The proof-of-work (PoW) algorithm enables one party to prove to others that it completed a task using computational power. This algorithm ensures the protection of honest contributions through punishing dishonest contributions and preventing attacks to the network when trying to reach a verifiable consensus. This is possible because attempts to manipulate the blockchain by passing off changes as honest would require a single actor reperforming as much work as the entire distributed network had to that point, and racing it in real time to overtake its aggregate.

Difficulty Adjustment

Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment assesses the difficulty of mining a Bitcoin block. It is measured in terms of computing power, where the harder it is to mine, the more computing power is required to mine a new block. Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment ensures that the rate of discovery of new blocks remains relatively constant. As Bitcoin attracts more miners over time, the network hash rate will also increase over time. As a result, in response to increases in network hash rate, it is necessary to make it harder to mine blocks to ensure that the rate of discovery of new blocks remains constant.

Native Unit of Monetary Value

As alluded to in the Bitcoin PoW algorithm discussion, Bitcoin can reward honest contributions and punish dishonest contributions. This necessitates the existence of a native unit of monetary value within Bitcoin’s protocol, as this is how it rewards honest contributions to the blockchain.

Lack of a Specifically Identifiable Founder

Bitcoin’s lack of a specifically identifiable founder allows it to be truly decentralised. This differentiates Bitcoin from other NBCAs, who have recognised founders that exert influence over their protocol. Founders may be able to change certain properties of the NBCA, such as its supply inflation or its ability to tax holders. Hence, a founder’s changes may negatively impact on the NBCA’s utility of money as a store of value, causing the NBCA to draw parallels to a fiat currency controlled by a central bank.

Fair Launch

The final Bitcoin idiosyncrasy not mentioned by Farrington et al is its fair launch. By definition, a fair launch for a digital asset is a launch that has no early access, enables the token to be governed by the community from the outset, and allows everyone to equally participate. Bitcoin had what is considered to be the fairest launch of any digital asset, due to the following reasons:

- There were no pre-mined coins. Therefore, no individual had access to Bitcoin prior to its launch.

- Satoshi Nakamoto informed the Cypherpunk community of Bitcoin’s launch 2 months prior to mining the Genesis block. This allowed for word-of-mouth to spread about Bitcoin’s launch, as well as community participation, review and input.

- Nakamoto did not demand a fee to participate in Bitcoin’s launch. This allowed everyone, regardless of their wealth, to participate in Bitcoin’s launch.

Bitcoin’s fair launch was important as it ensured that everyone had equal access to the token’s initial distribution. Thus, no individual or entity had an advantage over others in access to the token.

Risk

From a financial perspective, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) defines risk as “the degree of uncertainty and/or potential financial loss inherent in an investment decision.” Conversely, from an engineering perspective, an appropriate risk definition would be “a way to express both the probability of occurrence and the consequences arising from such occurrence”. Both definitions are necessary as Bitcoin is relevant both as a financial asset and a software project.

Within the context of Bitcoin, systematic risks are risks that affect the entire digital asset class. Conversely, idiosyncratic risks are risks that are specific to Bitcoin.

Introduction to Risk Framework Approaches

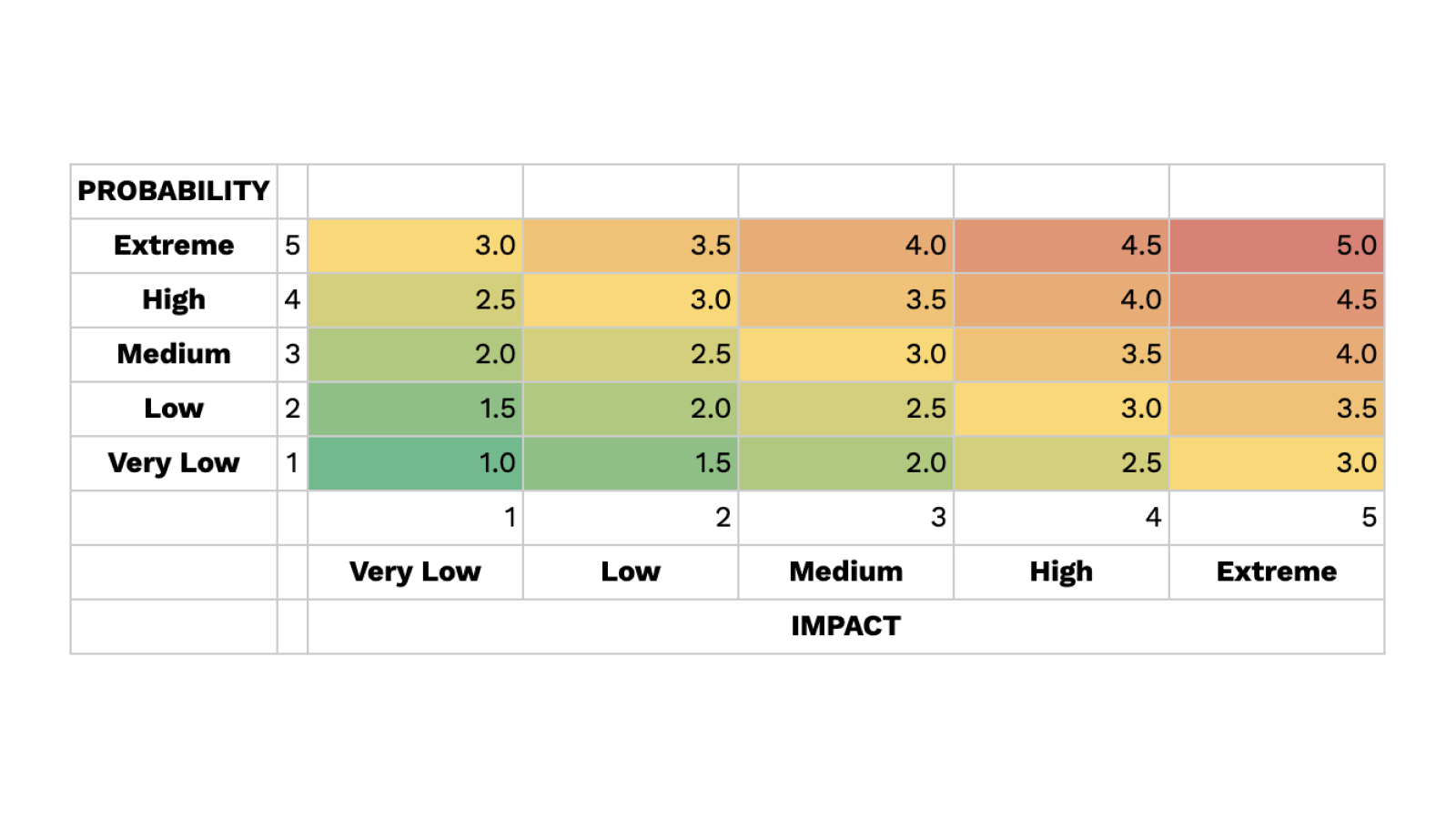

To analyse the magnitude of Bitcoin’s idiosyncratic risks, a risk framework needs to be applied.

The risk framework used below to analyse Bitcoin’s idiosyncratic risks was developed by Australia’s prudential regulator, the Australian Prudential and Regulation Authority (APRA). For each risk, the framework determines an overall risk level on the basis of two factors; the probability of failure, and the impact of failure.

For the purposes of this piece, the naming of the two factors will be altered to (i) the probability of the risk occurring, and (ii) the impact of the risk occurring.

The probability and impact of the risk occurring are both graded on a 5-point scale:

- Very low (1)

- Low (2)

- Medium (3)

- High (4)

- Extreme (5)

The overall risk rating will be the arithmetic average of the probability and impact ratings.

After development of an overall risk rating, a mitigation plan is determined for each risk. The purpose of a mitigation plan is to provide a clear understanding of the necessary actions needed to be taken to minimise the effects and chances of the risk occurring.

Lastly, a residual risk rating for each idiosyncratic risk will be determined. This rating describes how severe the risk is post-mitigation treatment. The higher the risk’s residual risk rating, the more severe the risk is, as no further mitigation is possible at this point. The residual risk ratings are determined based on the existence and effectiveness of the relevant risk mitigation plans, and they are graded as follows:

- Existence of risk mitigation plan, and near total mitigation (0.5)

- Existence of risk mitigation plan, and limited mitigation (between 0.5 and overall risk rating)

- Non-existence of risk mitigation plan (equal to overall risk rating)

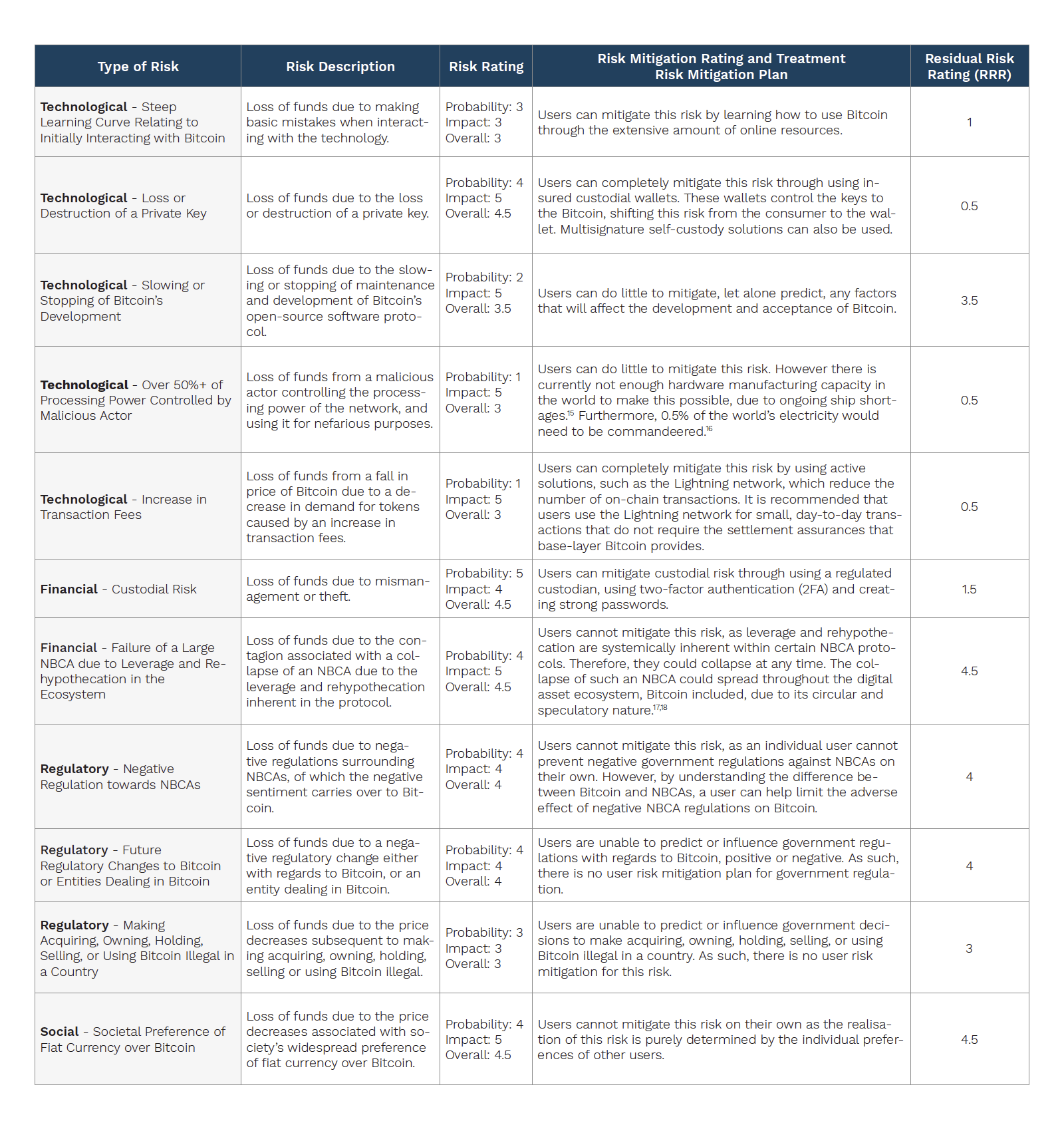

Bitcoin’s Idiosyncratic Risks

Bitcoin’s idiosyncratic risks can be classified into the following categories:

- Technological

- Financial

- Regulatory

- Social

The below table provides an assessment of Bitcoin’s idiosyncratic risks, mitigation techniques, and the residual risk after mitigation.

Conclusion

Bitcoin has idiosyncrasies that differentiate it from NBCAs, and idiosyncratic risks that have the potential to cause the user to lose funds. While Bitcoin is considered a high-risk asset, there are mitigation treatments that can be used, or which are being considered and implemented by developers, to reduce its overall idiosyncratic risk dramatically, whether through reducing the risk’s probability or the severity of impact.

The content, presentations and discussion topics covered in this material are intended for licensed financial advisers and institutional clients only and are not intended for use by retail clients. No representation, warranty or undertaking is given or made in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented. Except for any liability which cannot be excluded, Monochrome, its directors, officers, employees and agents disclaim all liability for any error or inaccuracy in this material or any loss or damage suffered by any person as a consequence of relying upon it. Monochrome advises that the views expressed in this material are not necessarily those of Monochrome or of any organisation Monochrome is associated with. Monochrome does not purport to provide legal or other expert advice in this material and if any such advice is required, you should obtain the services of a suitably qualified professional.

Related Articles

How to Value Bitcoin (2024 Update)

Valuing Bitcoin can be a challenge as, due to its abstract nature, there is “nothing to relate it to.” However, by shifting the lens through which we view Bitcoin, we can arrive at compelling theories through Metcalfe’s law, Stock-to-Flow, cost of production, market sizing and relating it to a technology start-up. Taken together, the following valuation models can be useful, though individually insufficient. Each model hosts criticisms, accommodating for improvements and adaptations.