Share

Learning Outcomes

In this piece, you will learn about the history of Bitcoin, including:

- Its early origins and creation.

- The basics of the underlying technology and functionality.

- The monetary problems it aims to solve.

- The evolution of Bitcoin narratives over time.

Foreword

As Bitcoin enters its second decade, it is opportune to reflect on its transformation from a monetary thought experiment, the first recorded transactional use being to buy pizza, into a fully-fledged financial ecosystem that has garnered significant interest, both from retail and institutional investors.

Digital assets constitute a market cap of US$2.1 trillion, with market leader Bitcoin boasting over 110 million users and around US$5 billion in daily settlement volume as of early September. Companies such as PayPal, Visa, and Square are integrating digital asset payment processing to preempt disruption; financial institutions such as Fidelity and Goldman Sachs are expanding their trading services to meet the surge in client demand; and, central banks from the Federal Reserve to the People’s Bank of China are developing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) of their own.

Despite this increase in adoption, various challenges remain for institutional investors to procure digital assets, whether as an investment or as a hedge against the broader macroeconomic environment. This document explores Bitcoin from the perspective of an institutional investor to strategize for what lies ahead in the digital asset market.

Bitcoin History

Origins

Bitcoin is an open-source monetary system created by Satoshi Nakamoto, a pseudonymous individual or group, who first detailed the underlying architecture in the 2008 whitepaper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”. Through its proposed digital timestamping technology, Satoshi envisioned a world in which digital settlements were executed without a trusted third party such as a bank or payment processor. Instead, these settlements would be verified and recorded in a public global ledger called the blockchain and supported by stakeholders of the Bitcoin protocol.

Solving a Database Problem

To fully appreciate blockchain as a solution, consider the monetary problem it endeavours to solve. Today, people can either transact with cash, or through “the banking system” via Point-of-Sale and online card payments, cheques, and bank transfers. Paying someone in cash is instant and final, but possible only when both parties are in proximity to each other. Bank transfers are usually only fast or instant when both sender and recipient are customers of the same bank (and accordingly, have balance records from the same database), otherwise transactions take longer as banks need to de-risk themselves from overdrawn accounts or double spending. Recent changes have seen groups of banks creating shared databases, allowing for fast or instant interbank transfers. Modern fintech start-ups also offer a partial solution by leveraging network effects to get some users on the same database, but users outside of these second-degree networks still face the same problem.

Blockchain solves this database problem, which has so far been mitigated using trusted third parties. It does so by distributing the database across many nodes, and where the security and accuracy of the database is not controlled by any entity or authority, but via encryption and code. Anyone with an internet connection can view all historical transactions made on Bitcoin from the moment of its inception. If you have copies of the same database and no one is in charge, however, how would you ascertain which copy of the database is accurate and most up-to-date?

Bitcoin Basics

In lieu of trust placed with a third party, Bitcoin leverages public key cryptography to facilitate communications between network participants without divulging sensitive information. Each network participant has addresses associated with a pair of public and private keys that are stored in a wallet. Only senders with a private key can ‘sign’ and authorize a transaction of Bitcoin to be sent from that address, but all users within the network can easily verify the signature using the sender’s public key.

Once new transactions are initiated, the blockchain is appended through a process called ‘mining’. Mining incorporates the following stages:

- New transactions are broadcasted to the entire Bitcoin network via nodes.

- Miners choose which transactions to include in the next block, often based on transaction fees.

- Miners then expend computational power to perform Proof-of-Work (PoW).

- When PoW is found, the miner broadcasts the new block throughout the network.

- Nodes validate the new block, and the process repeats.

The Bitcoin ecosystem’s growth over the past decade has been enabled by stakeholders with different roles. Specifically, they are:

- Users who transact with one another on the network and pay to have transactions finalized.

- Miners who incur costs to process transactions, in exchange for newly minted bitcoin.

- Nodes that run Bitcoin software to maintain a copy of the global ledger.

- Developers who maintain Bitcoin software that is executed by miners through ‘mining’.

The PoW exercise in mining maintains the security of the network. It is a consensus mechanism that requires miners to expend electrical energy (called ‘hash power’) in solving an arbitrary mathematical problem. By design, each problem takes about 10 minutes to solve, with the difficulty of the problem adjusting to maintain this solving rate as miners enter and exit the ecosystem. After mining a new block, the successful miner is rewarded with newly issued bitcoin and fees from transactions known as ‘mining rewards’. Newly issued bitcoins follow a schedule that halves every 210,000 blocks mined, approximately every 4 years. Blocks mined in 2009 rewarded miners with 50 Bitcoin, while each block mined today is rewarded with 6.25 Bitcoin. Only 21 million Bitcoin will ever be mined, after which miners will only be compensated by transaction fees. Because blocks are added sequentially to the blockchain and copies of the blockchain are distributed amongst nodes, it is incredibly difficult to attack the network. To do so, malicious actors would have to perform a “51% attack” in which they take control of more than half of the network’s hash rate to alter transactions on the blockchain. So far, there have been no successful 51% attacks on Bitcoin in its history.

What was Bitcoin Created for?

Like any nascent asset, the Bitcoin narrative has undergone an evolution since its inception in 2008. It was first recognized as another e-cash proof of concept when Satoshi circulated pre-release code amongst other revered members in the cryptography community. Initial reactions were lukewarm at best, as the community had seen b-money, Hashcash, and bit gold fail before Bitcoin. Skeptics fell silent in early 2009, when Satoshi successfully bootstrapped the network and mined the first few blocks. He initiated the first transaction of 10 Bitcoins to a fellow enthusiast Hal Finney, and kicked off momentum in the network.

Before long, the experimental internet money gained popularity amongst early adopters as a cheap P2P payments network, the most notable transaction being 10,000 Bitcoins for two large pizzas in 2010. This narrative both made sense and was necessary early on as usage in the network experienced exponential growth. Transaction fees were fractions of a cent at the time, contrasting the 6.38% global average charged by remittance companies. Due to block size constraints and growing demand, however, this narrative weakened as average transactions cost as high as US$55 during the peak of the 2017 bull market. Instead, other projects such as Bitcoin Cash and “layer two” solutions like Lightning Network have since attempted to gain market share in remittance, either through increasing block sizes or bidirectional payment channels.

Many critics of Bitcoin have also challenged its legitimacy, citing the use of cryptocurrencies as a medium of exchange in darknet marketplaces. This narrative was most prevalent in 2012-3 when it was revealed that the Silk Road had facilitated sales worth 9,519,664 BTC, equivalent to US$183m at time of sales, between February 2011 and its closure in July 2013. It is enticing to follow this line of thinking, since Bitcoin wallets are not registered to specific identities and early KYC requirements for crypto exchanges were loose at best. A closer look at the data, however, suggests that criminal activity represented only 0.34% of all cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2020, while 2 - 5% of global annual GDP is associated with illicit activity.

This means that criminal transactions using cryptocurrency are much more uncommon than fiat currency, both on a fractional and dollar value basis. Today, 99% of cryptocurrency transactions are performed through centralised exchanges, which are subject to Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-terrorism Financing regulation, similar to traditional financial institutions. Despite overwhelming data to suggest otherwise, this ‘criminal activity’ narrative is still unfortunately proffered by many respectable figures, including U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen.

When Bitcoin peaked in 2017, it was also viewed as a reserve currency for the entire digital market landscape. At the time, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) were commonplace, and week-old startup projects that offered little to no differentiation to one another were raising millions in capital. Retail traders wanted to partake in the upside of these alternatives to Bitcoin, but eventually were reminded of these projects’ outsized risks relative to Bitcoin. They quoted the prices of these alternative projects in satoshis, trading against Bitcoin with the aim of increasing their Bitcoin stack over time. The practice of having Bitcoin as the numeraire for the rest of the digital asset industry is still prevalent today amongst traders, businesses, and distributed networks that hold reserves in Bitcoin.

As one decade’s length of Bitcoin price data became available, it became apparent that its price was largely uncorrelated to other financial assets in the market. This asset became attractive to asset managers - Modern Portfolio Theory states that adding assets to a diversified portfolio with low correlations can decrease portfolio risk without sacrificing return. To illustrate in the table below, Bitcoin’s correlation with other global asset classes has proven to be low. Many proponents of this narrative are not overly preoccupied with owning Bitcoin per se - they simply want Bitcoin-flavored risk.

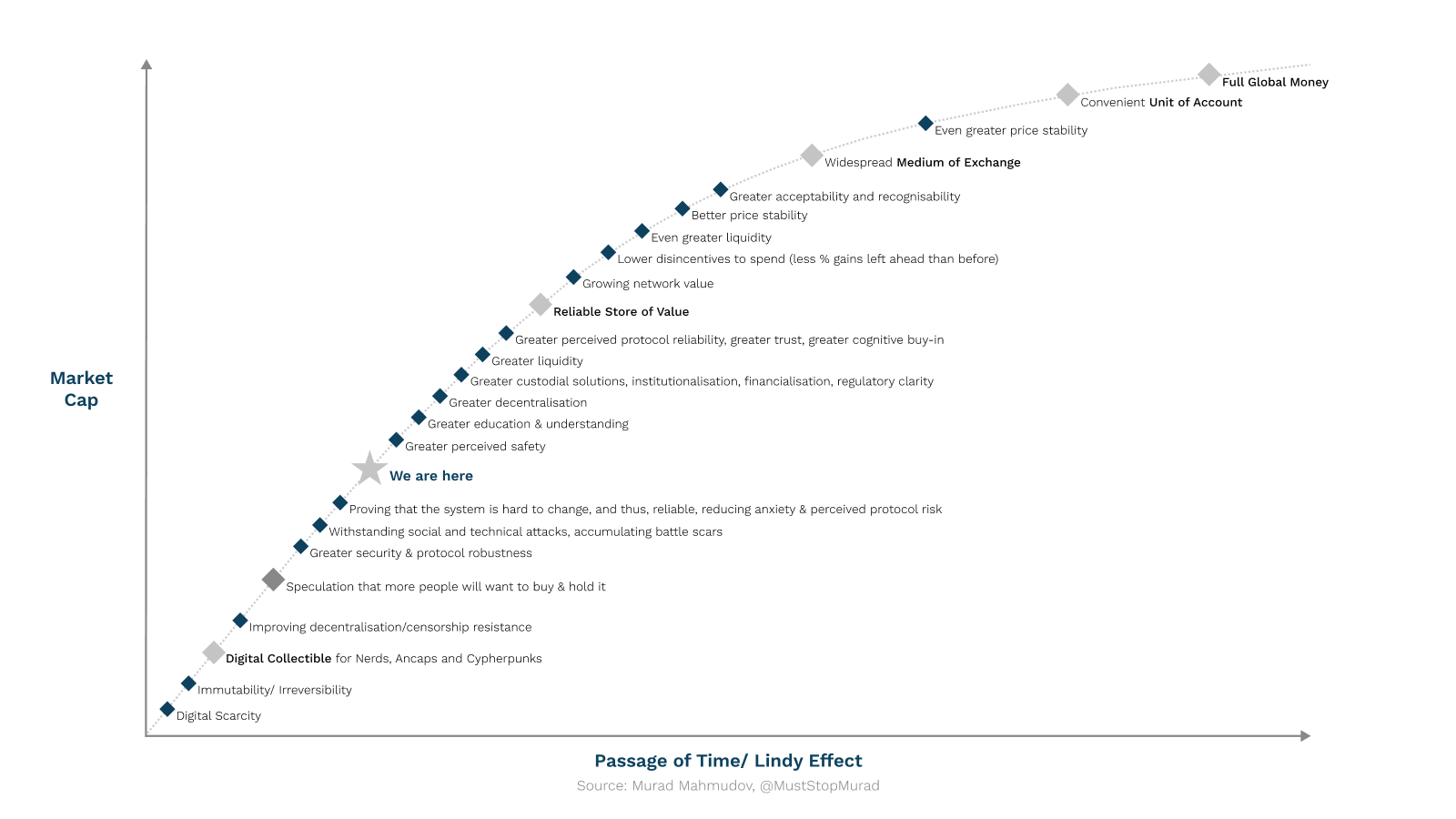

It is worthwhile noting that none of these narratives are necessarily incorrect - they simply form part of the story of Bitcoin to date. The below framework developed by Bitcoin analyst Murad Mahmudov provides another view on Bitcoin narrative evolution over time, and offers a glimpse into the future. Whilst this framework was first published in mid-2018, we are realistically just under half way between the 2018 “We are here” marker and the “Reliable Store of Value” marker, perhaps at “Greater Decentralisation”, and closely approaching “Greater regulatory clarity”. Volatility, and hence upside and downside risk, will likely stay high until after Bitcoin has evolved into a widespread medium of exchange, which could be well over a decade or more away, if ever at all.

The content, presentations and discussion topics covered in this material are intended for licensed financial advisers and institutional clients only and are not intended for use by retail clients. No representation, warranty or undertaking is given or made in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented. Except for any liability which cannot be excluded, Monochrome, its directors, officers, employees and agents disclaim all liability for any error or inaccuracy in this material or any loss or damage suffered by any person as a consequence of relying upon it. Monochrome advises that the views expressed in this material are not necessarily those of Monochrome or of any organisation Monochrome is associated with. Monochrome does not purport to provide legal or other expert advice in this material and if any such advice is required, you should obtain the services of a suitably qualified professional.

Related Articles

ESG Series - Governance Part 2: How Poor Governance Leads to Poor Outcomes

Since Bitcoin’s inception in 2008, the interest in Bitcoin and other digital currencies has grown significantly. Between 2010 which saw the very first exchange created which made it simpler to trade bitcoin, to the now arguably saturated marketplace for cryptocurrency exchanges, inadequate governance at cryptocurrency exchanges and other centralised crypto institutions has manifested in poor consumer outcomes.